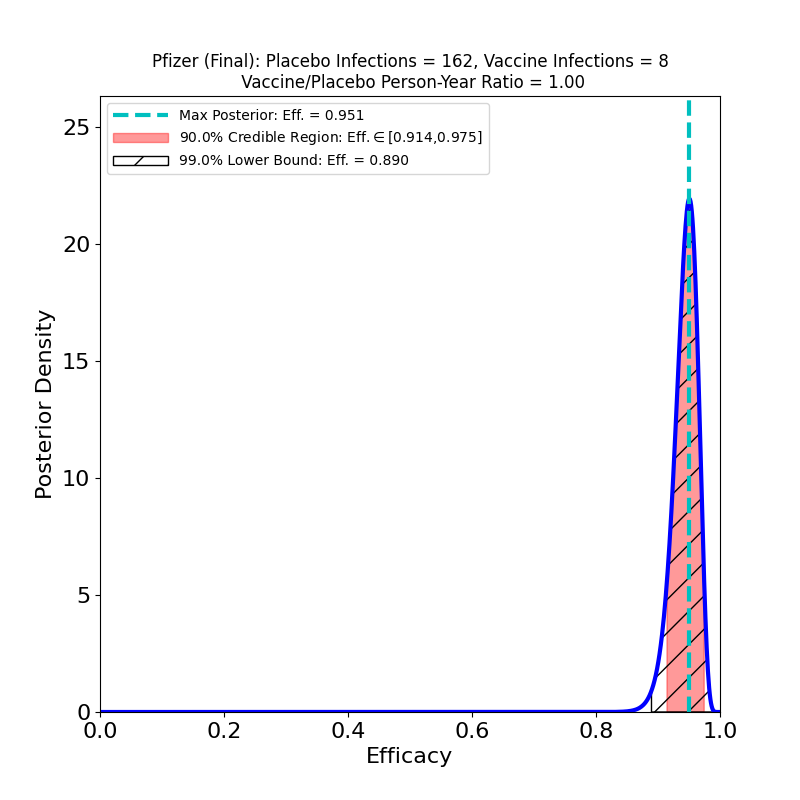

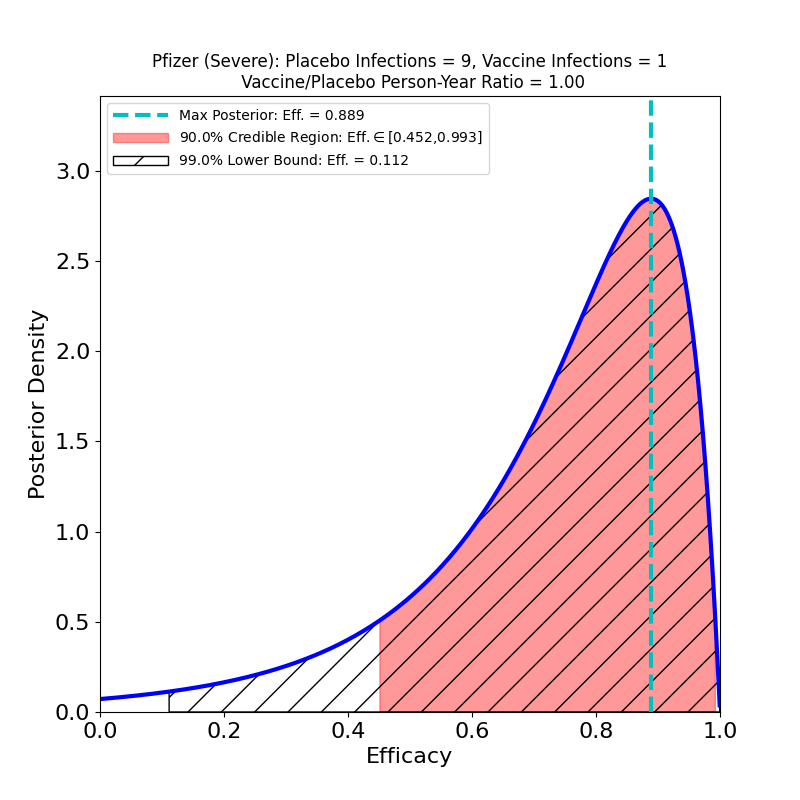

These plots result from the analysis of the Phase 3 trial data of Pfizer-BioNTech’s joint 2-dose mRNA-based vaccine, reported in this article.

Pfizer-BioNTech’s overall vaccine efficacy seems entirely comparable to Moderna’s. Interestingly, Pfizer-BioNTech’s “severe” protective efficacy seems rather disappointing, compared to Moderna’s. Note that this result does not show that Pfizer’s vaccine has lower efficacy against the severe disease than Moderna’s — only that Pfizer collected much worse evidence about severe disease efficacy than Moderna did. Pfizer only had 9 severe cases in its placebo group, as opposed to Moderna’s 30. This indicates that Pfizer was less diligent in recruiting trial participants with co-morbidities associated with the severe disease. In fact, the efficacy against severe disease could be the same as Moderna’s (why wouldn’t it be? the vaccines are very similar…), but Pfizer didn’t design their Phase 3 study in such a way to establish this.

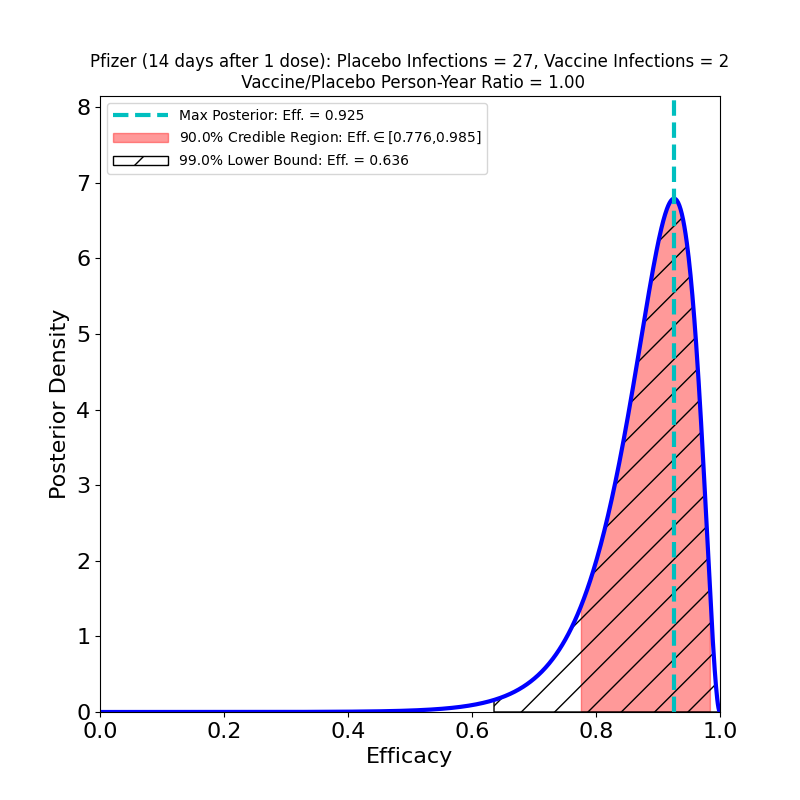

Update, 17 February 2021: In a letter to NEJM, D. Skowronski and G. De Serres drill down into the Pfizer data released to the FDA, extracting cases occurring between the first and second shot. They found something remarkable about the cases 14 days or more after shot 1, but before shot 2:

It turns out that this vaccine’s most likely efficacy after a single shot is 92%, not that different from the top-line efficacy number, and the 90% credible region is bounded below at 78%. The authors actually cite a 95% confidence interval (this is technically different from the credible regions reported on this site) as bounded below at 69%, a bit more conservative, but not inconsistent with the Bayesian result.

This is remarkable, but not that surprising. If you look at the now-famous Figure 13 of the Pfizer submission’s briefing document to the FDA, you can clearly see that by day 14 substantial protective efficacy has taken hold. There are better ways to analyze the uptake of efficacy than cutting the data in this way, but only if the Pfizer team were to release the full data for Figure 13. As it stands, Skowronski and De Serres have made an important discovery on the basis of a clever hack of the released data.

Their letter asserts that this evidence justifies delaying the second dose, so as to make early vaccinations available to more people. It’s a serious argument. I don’t feel qualified to assess its strength, although it does seem worth pointing out that this kind of data cannot speak to whether the protective efficacy of a 1-dose schedule declines faster than that from a 2-dose schedule, since all this data is from a short period after the first dose. In a pandemic-driven vaccination scarcity crisis, it may be worth taking the risk, or it may not. At a minimum I would say that the FDA has good general reasons not to support deviations from the only schedule that has been tested in an actual clinical trial. Exceptions should be extremely rare, and justified by extreme circumstances.

Update, 18 February 2021: Aaron Esser-Kahn (University of Chicago) shared the following with me, which I think is helpful to thinking about vaccine schedule changes:

I do think these arguments about 2nd dose delay are very complicated and not always appreciated by those not familiar with the complexity of the immune response . On first pass its very exciting that it protects, but what can’t be known without further experiment are the following (1) how long does it protect for? (2) Do the antibodies and cellular responses decrease rapidly? (3) What does the antibody and cellular selection look like? While I completely agree that a 3 week boost is arbitrary (having arbitrarily made this decision many times myself, I know it’s arbitrary), there are important considerations about the window in which B-Cell and T-cell selection are happening. Too long and you will get different cells and antibodies out. This could have longer term effects. So its always a questions of the devil you know vs. the one you don’t. One major risk you run is generating sub-optimal responses that allow viral selection in vaccinated individuals with weaker responses.