The FDA’s approval of Emergency Use Authorization of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine is being greeted ecstatically and uncritically by public officials and media. In my opinion, this is an indication that hardly anyone has actually looked at the data supplied by the company to the EUA committee, or read the briefing document in detail.

I wrote up a quick but careful analysis last week, which you may review here.

For present purposes, I’ll note only in passing the statistical illiteracy of journalistic celebrations of “85 percent efficacy against severe forms of COVID-19 and 100 percent efficacy against hospitalization and death” (NYT), figures that ignore both the considerable uncertainties in efficacy estimates and the carefully cherry-picked data that produces such numbers by nimble selections of geographical subregions of the trial, and by passing back and forth between results for 14 days and 28 days post-vaccine, whichever produces the better-seeming (though not actually better) result.

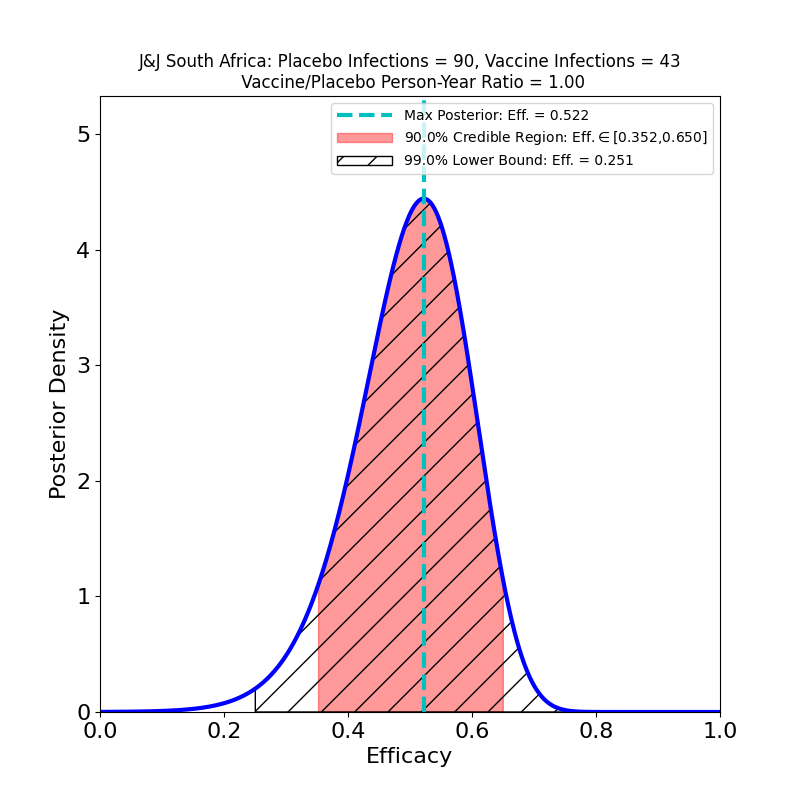

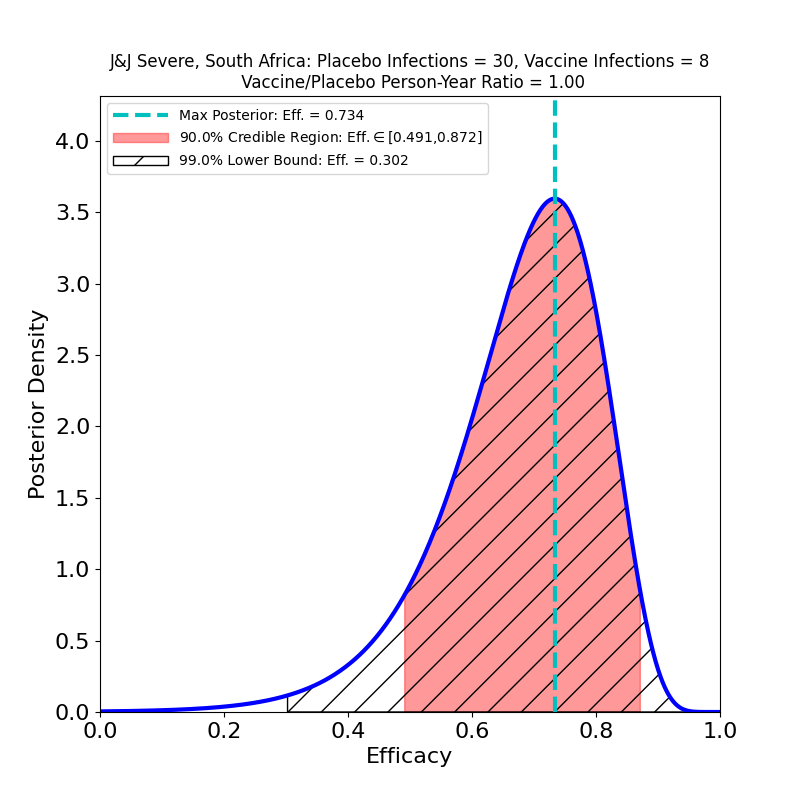

The point that I wish would draw notice is that the South African arm of the trial suggests that a variant crisis is imminent. The J&J vaccine is marginally effective at stopping transmission of the B.1.351 variant that is 95% prevalent in South Africa, and it’s efficacy against the severe disease could actually be as low as 50%. Here are the two relevant plots from that arm of the trial:

The right-hand figure offers some reassurance about “severe” disease (although if you think it means 80% you should not work as a science reporter). The left-hand figure, however, is extremely worrying. It says that the vaccine does nothing to restrain the spread of the virus, since all those “moderate” COVID-19 cases are shedding virus, and so are a nearly equal number of asymptomatic cases.

Here are some consequences:

B.1.135 Is The West’s Future Native Variant

It took less than 3 months for the original SARS-CoV-2 virus to travel from Wuhan to the U.S. and become an uncontrolled epidemic. It’s probably safe to assume that the freely-propagating B.1.135 variant, unrestrained by vaccination, will soon have high prevalence in the US and in Europe as well. It has mutated its way to a fitness advantage, so it will likely take over the SARS-CoV-2 genome within in a few months, probably by June at the latest.

It’s Not Just J&J’s Problem

I have no beef against J&J, and don’t mean to single the company out for criticism. There is plenty of evidence now that this is not just a J&J vaccine issue. We already know that the Novavax clinical trial had a South Africa arm that found the same thing. And South Africa has halted it’s rollout of the AstraZeneca vaccine, asserting that it “…offers minimal protection against mild and moderate cases”, as a consequence of the variant’s prevalence.

We don’t know how B.1.135 affects the efficacy of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, or that of the Sputnik V vaccine for that matter, since their clinical trials saw essentially zero prevalence of that variant. One may hope that since those vaccines appear to induce a more robust immune response, they may yield broader immunity against variants. But without new trials, all we can do is wait and find out.

Transmission Matters

Much of the media celebration appears to center on the ability of the J&J vaccine to prevent “severe” disease. As we saw above, even this ability is reduced in light of the advent of B.1.135. But ignoring the ineffectiveness of the vaccine at preventing transmission is madness. The probability of a mutation that increases transmissibility (or disease severity, for that matter) is proportional to the infection rate — the more cases per day, the higher the chances of a more dangerous mutation. The reason that we’re seeing proliferation of variants now, to an extent not noticeable during the March or August waves, is that the Winter wave case count eclipsed that of the other two — there have been many more mutation opportunities since October 2020 than there were before.

A vaccine is a tool for epidemic control, not a treatment or a cure. Focusing on prevention of the worst disease outcomes while ignoring transmission prevention totally misses the point. It’s tantamount to celebrating relief now, while ignoring the worse trouble to come.

A Silver Lining

The one reason that I can see not to panic now is that the next-generation vaccines that have come into being in the past year — mRNA and adenovirus vector — are reportedly very straightforward to re-target at new variants, and updated versions can be quickly produced at industrial scales, at least after current supply-chain bottlenecks are sorted out. What this means is that while everyone who gets a J&J, AZ, or Novavax vaccine now will be needing a booster by summer (and this may also be true for the Pfizer, Moderna, and Sputnik vaccines as well), at least there is reason to believe that such boosters will be widely available. For this reason, the public-health messaging on the J&J vaccine is correct: if you are offered a shot of the J&J vaccine, you should accept it. Just make sure you get a booster as soon as it is available.

The epidemic control strategy has to be to get total infection rates down (to slow the rise of newer, more dangerous variants), while rapidly developing, producing, distributing, and jabbing updated boosters to stamp out existing variants. And doing this everywhere, including in third-world nations that can’t afford to fund their own rapid-response anti-variant campaigns, because any large reservoir of transmitted virus is a potential source of newer, even more dangerous variants.

Moreover, the summer-booster messaging needs to start now. We all know how delicate public support for mass vaccination campaigns is, and how easily it can be poisoned by militantly ignorant, scientifically illiterate disinformation spread by the anti-vaxxer crowd. Those people will have a field day with rising-again infection rates among vaccinated individuals that are to be expected this summer and fall, unless there’s a comprehensive public health messaging program about variants and boosters. The sooner the better.

And reporters need to get smarter about reporting “victories” like this one, that carry seeds of future problems. When the victory turns out to be not as complete as first reported, and possibly even reversible, the consequences for public support of mass vaccination campaigns are unlikely to be good.

Will 2 doses of the Pfizer vaccine help with exposure to the B.1.135 variant? My Wife and I have had the first Pfizer shot and are scheduled to get the second in two weeks.

Grazie!!

Hi Seth.

Let me premise that I am not a (medical) doctor, and no medical advice from me should be taken as authoritative.

That said, I don’t think much is known about performance of the Pfizer (or Moderna) vaccines against this specific variant. It may perform well — it performs spectacularly against the classic variants, so perhaps its efficacy will be reduced to merely good. I wouldn’t trust it enough to go back to unmasked, un-distanced “normality”, especially if the South African variant becomes prevalent in the Northern Hemisphere (as I believe is likely). However, for now the Pfizer vaccine should, I believe, be sufficient to give individuals peace of mind about things like schools, shopping, travel etc.

The more people are vaccinated, the fewer opportunities for contagion, obviously, so a good perspective is that we vaccinate ourselves for the benefit of others as well as for our own — same as masking, really.

From a practical perspective, I would make sure to get an update booster for the later variants as soon as one is available. I feel it is likely that they will be rolled out this year.